http://xmodulo.com/linux-vs-windows-device-driver-model.html

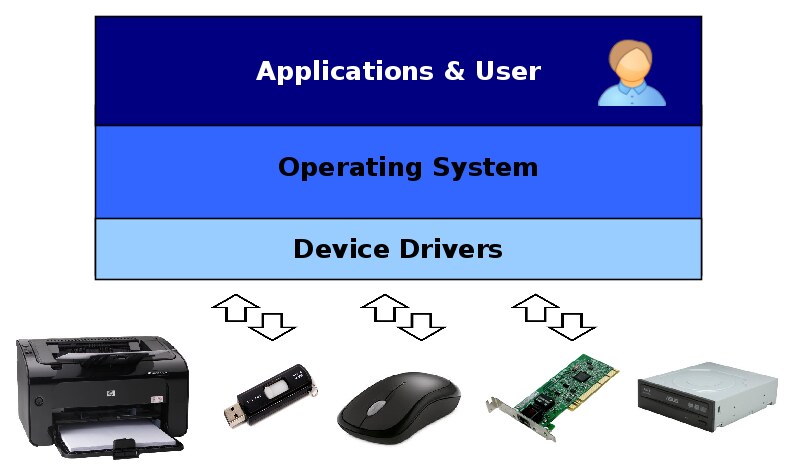

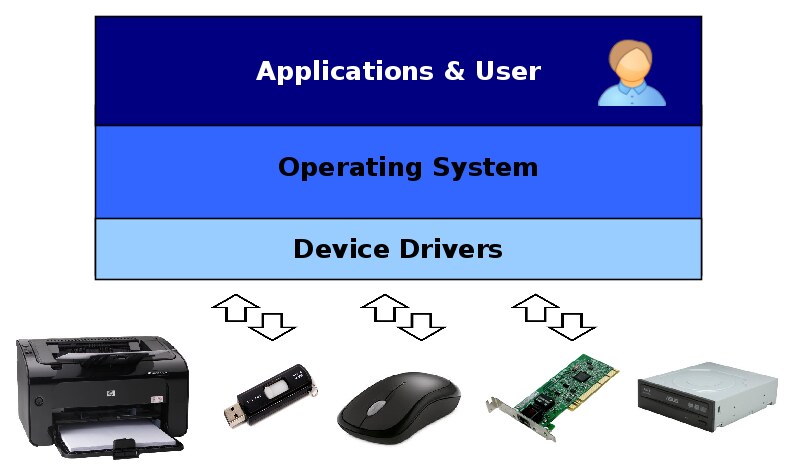

Device drivers are parts of the operating system that facilitate usage of hardware devices via certain programming interface so that software applications can control and operate the devices. As each driver is specific to a particular operating system, you need separate Linux, Windows, or Unix device drivers to enable the use of your device on different computers. This is why when hiring a driver developer or choosing an R&D service provider, it is important to look at their experience of developing drivers for various operating system platforms.

The first step in driver development is to understand the differences in the way each operating system handles its drivers, underlying driver model and architecture it uses, as well as available development tools. For example, Linux driver model is very different from the Windows one. While Windows facilitates separation of the driver development and OS development and combines drivers and OS via a set of ABI calls, Linux device driver development does not rely on any stable ABI or API, with the driver code instead being incorporated into the kernel. Each of these models has its own set of advantages and drawbacks, but it is important to know them all if you want to provide a comprehensive support for your device.

In this article we will compare Windows and Linux device drivers and explore the differences in terms of their architecture, APIs, build development, and distribution, in hopes of providing you with an insight on how to start writing device drivers for each of these operating systems.

Requests from applications are handled by a part of Windows kernel called IO manager which transforms them into IO Request Packets (IRPs) which are used to identify the request and convey data between driver layers.

WDM provides three kinds of drivers, which form three layers:

Modules export functions they provide and communicate by calling these functions and passing around arbitrary data structures. Requests from user applications come from the filesystem or networking level, and are converted into data structures as necessary. Modules can be stacked into layers, processing requests one after another, with some modules providing a common interface to a device family such as USB devices.

Linux device drivers support three kinds of devices:

As compared to Windows, Linux device driver lifetime is managed by kernel module's module_init and module_exit functions, which are called when the module is loaded or unloaded. They are responsible for registering the module to handle device requests using the internal kernel interfaces. The module has to create a device file (or a network interface), specify a numerical identifier of the device it wishes to manage, and register a number of callbacks to be called when the user interacts with the device file.

Windows device driver is notified about newly connected devices in its AddDevice callback. It then proceeds to create a device object used to identify this particular driver instance for the device. Depending on the driver kind, device object can be a Physical Device Object (PDO), Function Device Object (FDO), or a Filter Device Object (FIDO). Device objects can be stacked, with a PDO in the bottom.

Device objects exist for the whole time the device is connected to the computer. DeviceExtension structure can be used to associate global data with a device object.

Device objects can have names of the form \Device\DeviceName, which are used by the system to identify and locate them. An application opens a file with such name using CreateFile API function, obtaining a handle, which then can be used to interact with the device.

However, usually only PDOs have distinct names. Unnamed devices can be accessed via device class interfaces. The device driver registers one or more interfaces identified by 128-bit globally unique identifiers (GUIDs). User applications can then obtain a handle to such device using known GUIDs.

Registering devices on Linux

On Linux user applications access the devices via file system entries, usually located in the /dev directory. The module creates all necessary entries during module initialization by calling kernel functions like register_chrdev. An application issues an open system call to obtain a file descriptor, which is then used to interact with the device. This call (and further system calls with the returned descriptor like read, write, or close) are then dispatched to callback functions installed by the module into structures like file_operations or block_device_operations.

The device driver module is responsible for allocating and maintaining any data structures necessary for its operation. A file structure passed into the file system callbacks has a private_data field, which can be used to store a pointer to driver-specific data. The block device and network interface APIs also provide similar fields.

While applications use file system nodes to locate devices, Linux uses a concept of major and minor numbers to identify devices and their drivers internally. A major number is used to identify device drivers, while a minor number is used by the driver to identify devices managed by it. The driver has to register itself in order to manage one or more fixed major numbers, or ask the system to allocate some unused number for it.

Currently, Linux uses 32-bit values for major-minor pairs, with 12 bits allocated for the major number allowing up to 4096 distinct drivers. The major-minor pairs are distinct for character and block devices, so a character device and a block device can use the same pair without conflicts. Network interfaces are identified by symbolic names like eth0, which are again distinct from major-minor numbers of both character and block devices.

Support for Buffered IO is a built-in feature of WDM. The buffer is accessible to the device driver via the AssociatedIrp.SystemBuffer field of the IRP structure. The driver simply reads from or writes to this buffer when it needs to communicate with the userspace.

Direct IO on Windows is mediated by memory descriptor lists (MDLs). These are semi-opaque structures accessible via MdlAddress field of the IRP. They are used to locate the physical address of the buffer allocated by the user application and pinned for the duration of the IO request.

The third option for data transfer on Windows is called METHOD_NEITHER.

In this case the kernel simply passes the virtual addresses of

user-space input and output buffers to the driver, without validating

them or ensuring that they are mapped into physical memory accessible by

the device driver. The device driver is responsible for handling the

details of the data transfer.

Driver IO modes on Linux

Linux provides a number of functions like clear_user, copy_to_user, strncpy_from_user, and some others to perform buffered data transfers between the kernel and user memory. These functions validate pointers to data buffers and handle all details of the data transfer by safely copying the data buffer between memory regions.

However, drivers for block devices operate on entire data blocks of known size, which can be simply moved between the kernel and user address spaces without copying them. This case is automatically handled by Linux kernel for all block device drivers. The block request queue takes care of transferring data blocks without excess copying, and Linux system call interface takes care of converting file system requests into block requests.

Finally, the device driver can allocate some memory pages from kernel address space (which is non-swappable) and then use the remap_pfn_range function to map the pages directly into the address space of the user process. The application can then obtain the virtual address of this buffer and use it to communicate with the device driver.

Windows is a closed-source operating system. Microsoft provides a Windows Driver Kit to facilitate Windows device driver development by non-Microsoft vendors. The kit contains all that is necessary to build, debug, verify, and package device drivers for Windows.

Windows Driver Model defines a clean interface framework for device drivers. Windows maintains source and binary compatibility of these interfaces. Compiled WDM drivers are generally forward-compatible: that is, an older driver can run on a newer system as is, without being recompiled, but of course it will not have access to the new features provided by the OS. However, drivers are not guaranteed to be backward-compatible.

Linux source code

In comparison to Windows, Linux is an open-source operating system, thus the entire source code of Linux is the SDK for driver development. There is no formal framework for device drivers, but Linux kernel includes numerous subsystems that provide common services like driver registration. The interfaces to these subsystems are described in kernel header files.

While Linux does have defined interfaces, these interfaces are not stable by design. Linux does not provide any guarantees about forward or backward compatibility. Device drivers are required to be recompiled to work with different kernel versions. No stability guarantees allow rapid development of Linux kernel as developers do not have to support older interfaces and can use the best approach to solve the problems at hand.

Such ever-changing environment does not pose any problems when writing in-tree drivers for Linux, as they are a part of the kernel source, because they are updated along with the kernel itself. However, closed-source drivers must be developed separately, out-of-tree, and they must be maintained to support different kernel versions. Thus Linux encourages device driver developers to maintain their drivers in-tree.

Linux uses Makefiles as a build system for both in-tree and out-of-tree device drivers. Linux build system is quite developed and usually a device driver needs no more than a handful of lines to produce a working binary. Developers can use any IDE as long as it can handle Linux source code base and run make, or they can easily compile drivers manually from terminal.

Linux documentation is not as descriptive, but this is alleviated with the whole source code of Linux being available to driver developers. The Documentation directory in the source tree documents some of the Linux subsystems, but there are multiple books concerning Linux device driver development and Linux kernel overviews, which are much more elaborate.

Linux does not provide designated samples of device drivers, but the source code of existing production drivers is available and can be used as a reference for developing new device drivers.

Windows supports interactive debugging via its kernel-level debugger WinDbg. This requires two machines connected via a serial port: a computer to run the debugged kernel, and another one to run the debugger and control the operating system being debugged. Windows Driver Kit includes debugging symbols for Windows kernel so Windows data structures will be partially visible in the debugger.

Linux also supports interactive debugging by means of KDB and KGDB. Debugging support can be built into the kernel and enabled at boot time. After that one can either debug the system directly via a physical keyboard, or connect to it from another machine via a serial port. KDB offers a simple command-line interface and it is the only way to debug the kernel on the same machine. However, KDB lacks source-level debugging support. KGDB provides a more complex interface via a serial port. It enables usage of standard application debuggers like GDB for debugging Linux kernel just like any other userspace application.

When a new device is plugged into the computer, Windows looks though

installed drivers and loads an appropriate one. The driver will be automatically unloaded as soon as the device is removed.

On Linux some drivers are built into the kernel and stay permanently loaded. Non-essential ones are built as kernel modules, which are usually stored in the /lib/modules/kernel-version directory. This directory also contains various configuration files, like modules.dep describing dependencies between kernel modules.

While Linux kernel can load some of the modules at boot time itself, generally module loading is supervised by user-space applications. For example, init process may load some modules during system initialization, and the udev daemon is responsible for tracking the newly plugged devices and loading appropriate modules for them.

However, Linux does not provide a stable binary interface so it is necessary to recompile and update all necessary device drivers with each kernel update. Obviously, device drivers, which are built into the kernel are updated automatically, but out-of-tree modules pose a slight problem. The task of maintaining up-to-date module binaries is usually solved with DKMS: a service that automatically rebuilds all registered kernel modules when a new kernel version is installed.

Linux kernel can also be configured to verify signatures of kernel modules being loaded and disallow untrusted ones. The set of public keys trusted by the kernel is fixed at the build time and is fully configurable. The strictness of checks performed by the kernel is also configurable at build time and ranges from simply issuing warnings for untrusted modules to refusing to load anything with doubtful validity.

On the other hand, Linux does not constrain device driver developers with frameworks and the source code of the kernel and production device drivers can be just as helpful in the right hands. The lack of interface stability also has an implications as it means that up-to-date device drivers are always using the latest interfaces and the kernel itself carries lesser burden of backwards compatibility, which results in even cleaner code.

Knowing these differences as well as specifics for each system is a crucial first step in providing effective driver development and support for your devices. We hope that this Windows and Linux device driver development comparison was helpful in understanding them, and will serve as a great starting point in your study of device driver development process.

Device drivers are parts of the operating system that facilitate usage of hardware devices via certain programming interface so that software applications can control and operate the devices. As each driver is specific to a particular operating system, you need separate Linux, Windows, or Unix device drivers to enable the use of your device on different computers. This is why when hiring a driver developer or choosing an R&D service provider, it is important to look at their experience of developing drivers for various operating system platforms.

The first step in driver development is to understand the differences in the way each operating system handles its drivers, underlying driver model and architecture it uses, as well as available development tools. For example, Linux driver model is very different from the Windows one. While Windows facilitates separation of the driver development and OS development and combines drivers and OS via a set of ABI calls, Linux device driver development does not rely on any stable ABI or API, with the driver code instead being incorporated into the kernel. Each of these models has its own set of advantages and drawbacks, but it is important to know them all if you want to provide a comprehensive support for your device.

In this article we will compare Windows and Linux device drivers and explore the differences in terms of their architecture, APIs, build development, and distribution, in hopes of providing you with an insight on how to start writing device drivers for each of these operating systems.

1. Device Driver Architecture

Windows device driver architecture is different from the one used in Linux drivers, with either of them having their own pros and cons. Differences are mainly influenced by the fact that Windows is a closed-source OS while Linux is open-source. Comparison of the Linux and Windows device driver architectures will help us understand the core differences behind Windows and Linux drivers.1.1. Windows driver architecture

While Linux kernel is distributed with drivers themselves, Windows kernel does not include device drivers. Instead, modern Windows device drivers are written using the Windows Driver Model (WDM) which fully supports plug-and-play and power management so that the drivers can be loaded and unloaded as necessary.Requests from applications are handled by a part of Windows kernel called IO manager which transforms them into IO Request Packets (IRPs) which are used to identify the request and convey data between driver layers.

WDM provides three kinds of drivers, which form three layers:

- Filter drivers provide optional additional processing of IRPs.

- Function drivers are the main drivers that implement interfaces to individual devices.

- Bus drivers service various adapters and bus controllers that host devices.

1.2. Linux driver architecture

The core difference in Linux device driver architecture as compared to the Windows one is that Linux does not have a standard driver model or a clean separation into layers. Each device driver is usually implemented as a module that can be loaded and unloaded into the kernel dynamically. Linux provides means for plug-and-play support and power management so that drivers can use them to manage devices correctly, but this is not a requirement.Modules export functions they provide and communicate by calling these functions and passing around arbitrary data structures. Requests from user applications come from the filesystem or networking level, and are converted into data structures as necessary. Modules can be stacked into layers, processing requests one after another, with some modules providing a common interface to a device family such as USB devices.

Linux device drivers support three kinds of devices:

- Character devices which implement a byte stream interface.

- Block devices which host filesystems and perform IO with multibyte blocks of data.

- Network interfaces which are used for transferring data packets through the network.

2. Device Driver APIs

Both Linux and Windows driver APIs are event-driven: the driver code executes only when some event happens: either when user applications want something from the device, or when the device has something to tell to the OS.2.1. Initialization

On Windows, drivers are represented by a DriverObject structure which is initialized during the execution of the DriverEntry function. This entry point also registers a number of callbacks to react to device addition and removal, driver unloading, and handling the incoming IRPs. Windows creates a device object when a device is connected, and this device object handles all application requests on behalf of the device driver.As compared to Windows, Linux device driver lifetime is managed by kernel module's module_init and module_exit functions, which are called when the module is loaded or unloaded. They are responsible for registering the module to handle device requests using the internal kernel interfaces. The module has to create a device file (or a network interface), specify a numerical identifier of the device it wishes to manage, and register a number of callbacks to be called when the user interacts with the device file.

2.2. Naming and claiming devices

Registering devices on WindowsWindows device driver is notified about newly connected devices in its AddDevice callback. It then proceeds to create a device object used to identify this particular driver instance for the device. Depending on the driver kind, device object can be a Physical Device Object (PDO), Function Device Object (FDO), or a Filter Device Object (FIDO). Device objects can be stacked, with a PDO in the bottom.

Device objects exist for the whole time the device is connected to the computer. DeviceExtension structure can be used to associate global data with a device object.

Device objects can have names of the form \Device\DeviceName, which are used by the system to identify and locate them. An application opens a file with such name using CreateFile API function, obtaining a handle, which then can be used to interact with the device.

However, usually only PDOs have distinct names. Unnamed devices can be accessed via device class interfaces. The device driver registers one or more interfaces identified by 128-bit globally unique identifiers (GUIDs). User applications can then obtain a handle to such device using known GUIDs.

Registering devices on Linux

On Linux user applications access the devices via file system entries, usually located in the /dev directory. The module creates all necessary entries during module initialization by calling kernel functions like register_chrdev. An application issues an open system call to obtain a file descriptor, which is then used to interact with the device. This call (and further system calls with the returned descriptor like read, write, or close) are then dispatched to callback functions installed by the module into structures like file_operations or block_device_operations.

The device driver module is responsible for allocating and maintaining any data structures necessary for its operation. A file structure passed into the file system callbacks has a private_data field, which can be used to store a pointer to driver-specific data. The block device and network interface APIs also provide similar fields.

While applications use file system nodes to locate devices, Linux uses a concept of major and minor numbers to identify devices and their drivers internally. A major number is used to identify device drivers, while a minor number is used by the driver to identify devices managed by it. The driver has to register itself in order to manage one or more fixed major numbers, or ask the system to allocate some unused number for it.

Currently, Linux uses 32-bit values for major-minor pairs, with 12 bits allocated for the major number allowing up to 4096 distinct drivers. The major-minor pairs are distinct for character and block devices, so a character device and a block device can use the same pair without conflicts. Network interfaces are identified by symbolic names like eth0, which are again distinct from major-minor numbers of both character and block devices.

2.3. Exchanging data

Both Linux and Windows support three ways of transferring data between user-level applications and kernel-level drivers:- Buffered Input-Output which uses buffers managed by the kernel. For write operations the kernel copies data from a user-space buffer into a kernel-allocated buffer, and passes it to the device driver. Reads are the same, with kernel copying data from a kernel buffer into the buffer provided by the application.

- Direct Input-Output which does not involve copying. Instead, the kernel pins a user-allocated buffer in physical memory so that it remains there without being swapped out while data transfer is in progress.

- Memory mapping can also be arranged by the kernel so that the kernel and user space applications can access the same pages of memory using distinct addresses.

Support for Buffered IO is a built-in feature of WDM. The buffer is accessible to the device driver via the AssociatedIrp.SystemBuffer field of the IRP structure. The driver simply reads from or writes to this buffer when it needs to communicate with the userspace.

Direct IO on Windows is mediated by memory descriptor lists (MDLs). These are semi-opaque structures accessible via MdlAddress field of the IRP. They are used to locate the physical address of the buffer allocated by the user application and pinned for the duration of the IO request.

Driver IO modes on Linux

Linux provides a number of functions like clear_user, copy_to_user, strncpy_from_user, and some others to perform buffered data transfers between the kernel and user memory. These functions validate pointers to data buffers and handle all details of the data transfer by safely copying the data buffer between memory regions.

However, drivers for block devices operate on entire data blocks of known size, which can be simply moved between the kernel and user address spaces without copying them. This case is automatically handled by Linux kernel for all block device drivers. The block request queue takes care of transferring data blocks without excess copying, and Linux system call interface takes care of converting file system requests into block requests.

Finally, the device driver can allocate some memory pages from kernel address space (which is non-swappable) and then use the remap_pfn_range function to map the pages directly into the address space of the user process. The application can then obtain the virtual address of this buffer and use it to communicate with the device driver.

3. Device Driver Development Environment

3.1. Device driver frameworks

Windows Driver KitWindows is a closed-source operating system. Microsoft provides a Windows Driver Kit to facilitate Windows device driver development by non-Microsoft vendors. The kit contains all that is necessary to build, debug, verify, and package device drivers for Windows.

Windows Driver Model defines a clean interface framework for device drivers. Windows maintains source and binary compatibility of these interfaces. Compiled WDM drivers are generally forward-compatible: that is, an older driver can run on a newer system as is, without being recompiled, but of course it will not have access to the new features provided by the OS. However, drivers are not guaranteed to be backward-compatible.

Linux source code

In comparison to Windows, Linux is an open-source operating system, thus the entire source code of Linux is the SDK for driver development. There is no formal framework for device drivers, but Linux kernel includes numerous subsystems that provide common services like driver registration. The interfaces to these subsystems are described in kernel header files.

While Linux does have defined interfaces, these interfaces are not stable by design. Linux does not provide any guarantees about forward or backward compatibility. Device drivers are required to be recompiled to work with different kernel versions. No stability guarantees allow rapid development of Linux kernel as developers do not have to support older interfaces and can use the best approach to solve the problems at hand.

Such ever-changing environment does not pose any problems when writing in-tree drivers for Linux, as they are a part of the kernel source, because they are updated along with the kernel itself. However, closed-source drivers must be developed separately, out-of-tree, and they must be maintained to support different kernel versions. Thus Linux encourages device driver developers to maintain their drivers in-tree.

3.2. Build system for device drivers

Windows Driver Kit adds driver development support for Microsoft Visual Studio, and includes a compiler used to build the driver code. Developing Windows device drivers is not much different from developing a user-space application in an IDE. Microsoft also provides an Enterprise Windows Driver Kit, which enables command-line build environment similar to the one of Linux.Linux uses Makefiles as a build system for both in-tree and out-of-tree device drivers. Linux build system is quite developed and usually a device driver needs no more than a handful of lines to produce a working binary. Developers can use any IDE as long as it can handle Linux source code base and run make, or they can easily compile drivers manually from terminal.

3.3. Documentation support

Windows has excellent documentation support for driver development. Windows Driver Kit includes documentation and sample driver code, abundant information about kernel interfaces is available via MSDN, and there exist numerous reference and guide books on driver development and Windows internals.Linux documentation is not as descriptive, but this is alleviated with the whole source code of Linux being available to driver developers. The Documentation directory in the source tree documents some of the Linux subsystems, but there are multiple books concerning Linux device driver development and Linux kernel overviews, which are much more elaborate.

Linux does not provide designated samples of device drivers, but the source code of existing production drivers is available and can be used as a reference for developing new device drivers.

3.4. Debugging support

Both Linux and Windows have logging facilities that can be used to trace-debug driver code. On Windows one would use DbgPrint function for this, while on Linux the function is called printk. However, not every problem can be resolved by using only logging and source code. Sometimes breakpoints are more useful as they allow to examine the dynamic behavior of the driver code. Interactive debugging is also essential for studying the reasons of crashes.Windows supports interactive debugging via its kernel-level debugger WinDbg. This requires two machines connected via a serial port: a computer to run the debugged kernel, and another one to run the debugger and control the operating system being debugged. Windows Driver Kit includes debugging symbols for Windows kernel so Windows data structures will be partially visible in the debugger.

Linux also supports interactive debugging by means of KDB and KGDB. Debugging support can be built into the kernel and enabled at boot time. After that one can either debug the system directly via a physical keyboard, or connect to it from another machine via a serial port. KDB offers a simple command-line interface and it is the only way to debug the kernel on the same machine. However, KDB lacks source-level debugging support. KGDB provides a more complex interface via a serial port. It enables usage of standard application debuggers like GDB for debugging Linux kernel just like any other userspace application.

4. Distributing Device Drivers

4.1. Installing device drivers

On Windows installed drivers are described by text files called INF files, which are typically stored in C:\Windows\INF directory. These files are provided by the driver vendor and define which devices are serviced by the driver, where to find the driver binaries, the version of the driver, etc.When a new device is plugged into the computer, Windows looks though

installed drivers and loads an appropriate one. The driver will be automatically unloaded as soon as the device is removed.

On Linux some drivers are built into the kernel and stay permanently loaded. Non-essential ones are built as kernel modules, which are usually stored in the /lib/modules/kernel-version directory. This directory also contains various configuration files, like modules.dep describing dependencies between kernel modules.

While Linux kernel can load some of the modules at boot time itself, generally module loading is supervised by user-space applications. For example, init process may load some modules during system initialization, and the udev daemon is responsible for tracking the newly plugged devices and loading appropriate modules for them.

4.2. Updating device drivers

Windows provides a stable binary interface for device drivers so in some cases it is not necessary to update driver binaries together with the system. Any necessary updates are handled by the Windows Update service, which is responsible for locating, downloading, and installing up-to-date versions of drivers appropriate for the system.However, Linux does not provide a stable binary interface so it is necessary to recompile and update all necessary device drivers with each kernel update. Obviously, device drivers, which are built into the kernel are updated automatically, but out-of-tree modules pose a slight problem. The task of maintaining up-to-date module binaries is usually solved with DKMS: a service that automatically rebuilds all registered kernel modules when a new kernel version is installed.

4.3. Security considerations

All Windows device drivers must be digitally signed before Windows loads them. It is okay to use self-signed certificates during development, but driver packages distributed to end users must be signed with valid certificates trusted by Microsoft. Vendors can obtain a Software Publisher Certificate from any trusted certificate authority authorized by Microsoft. This certificate is then cross-signed by Microsoft and the resulting cross-certificate is used to sign driver packages before the release.Linux kernel can also be configured to verify signatures of kernel modules being loaded and disallow untrusted ones. The set of public keys trusted by the kernel is fixed at the build time and is fully configurable. The strictness of checks performed by the kernel is also configurable at build time and ranges from simply issuing warnings for untrusted modules to refusing to load anything with doubtful validity.

5. Conclusion

As shown above, Windows and Linux device driver infrastructure have some things in common, such as approaches to API, but many more details are rather different. The most prominent differences stem from the fact that Windows is a closed-source operating system developed by a commercial corporation. This is what makes good, documented, stable driver ABI and formal frameworks a requirement for Windows while on Linux it would be more of a nice addition to the source code. Documentation support is also much more developed in Windows environment as Microsoft has resources necessary to maintain it.On the other hand, Linux does not constrain device driver developers with frameworks and the source code of the kernel and production device drivers can be just as helpful in the right hands. The lack of interface stability also has an implications as it means that up-to-date device drivers are always using the latest interfaces and the kernel itself carries lesser burden of backwards compatibility, which results in even cleaner code.

Knowing these differences as well as specifics for each system is a crucial first step in providing effective driver development and support for your devices. We hope that this Windows and Linux device driver development comparison was helpful in understanding them, and will serve as a great starting point in your study of device driver development process.

No comments:

Post a Comment